This asteroid is spilling secrets about the origin of life on Earth

Grab-and-go missions to asteroids have provided some of the most scientifically valuable samples since the Apollo missions—and they’re shaking up the search for life beyond Earth.

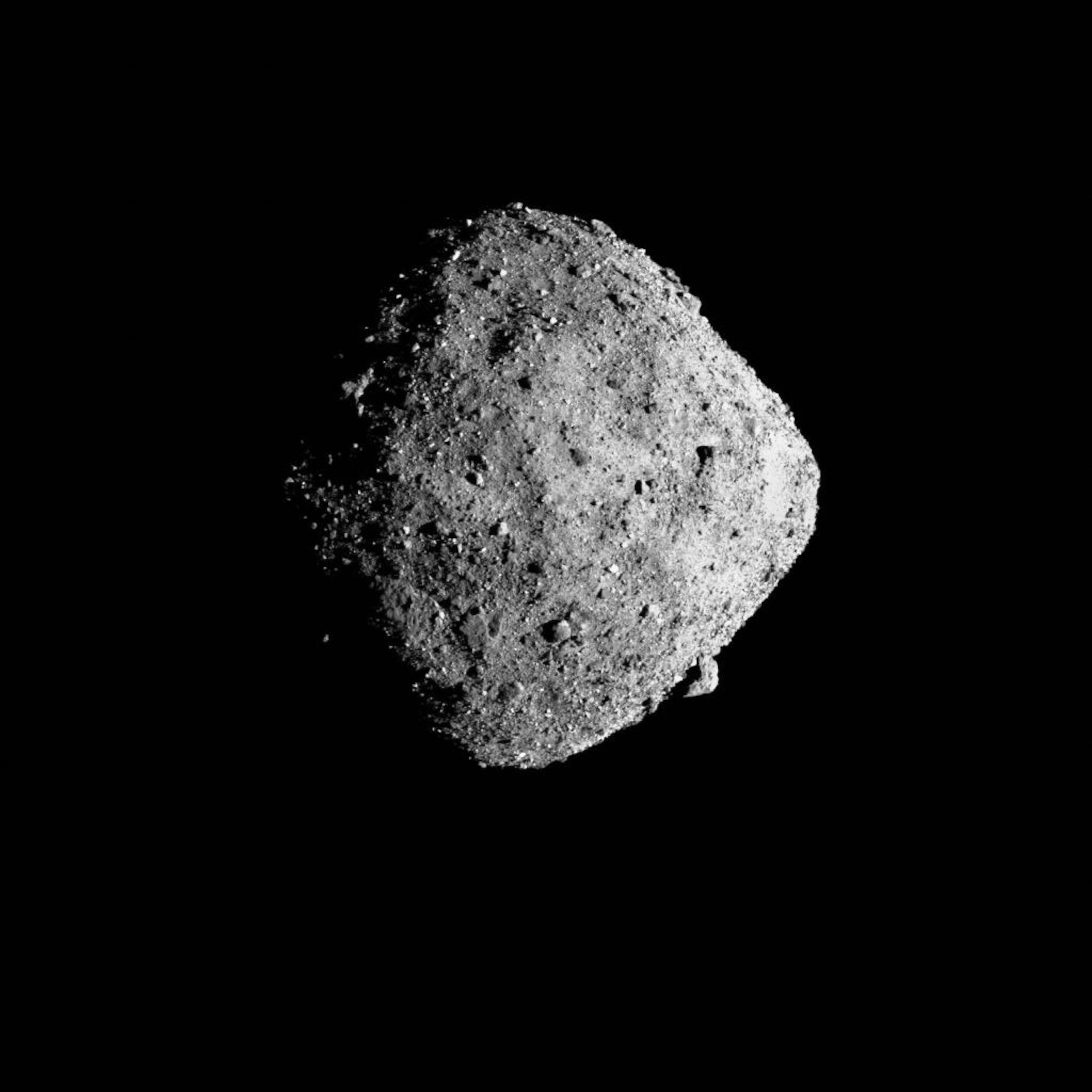

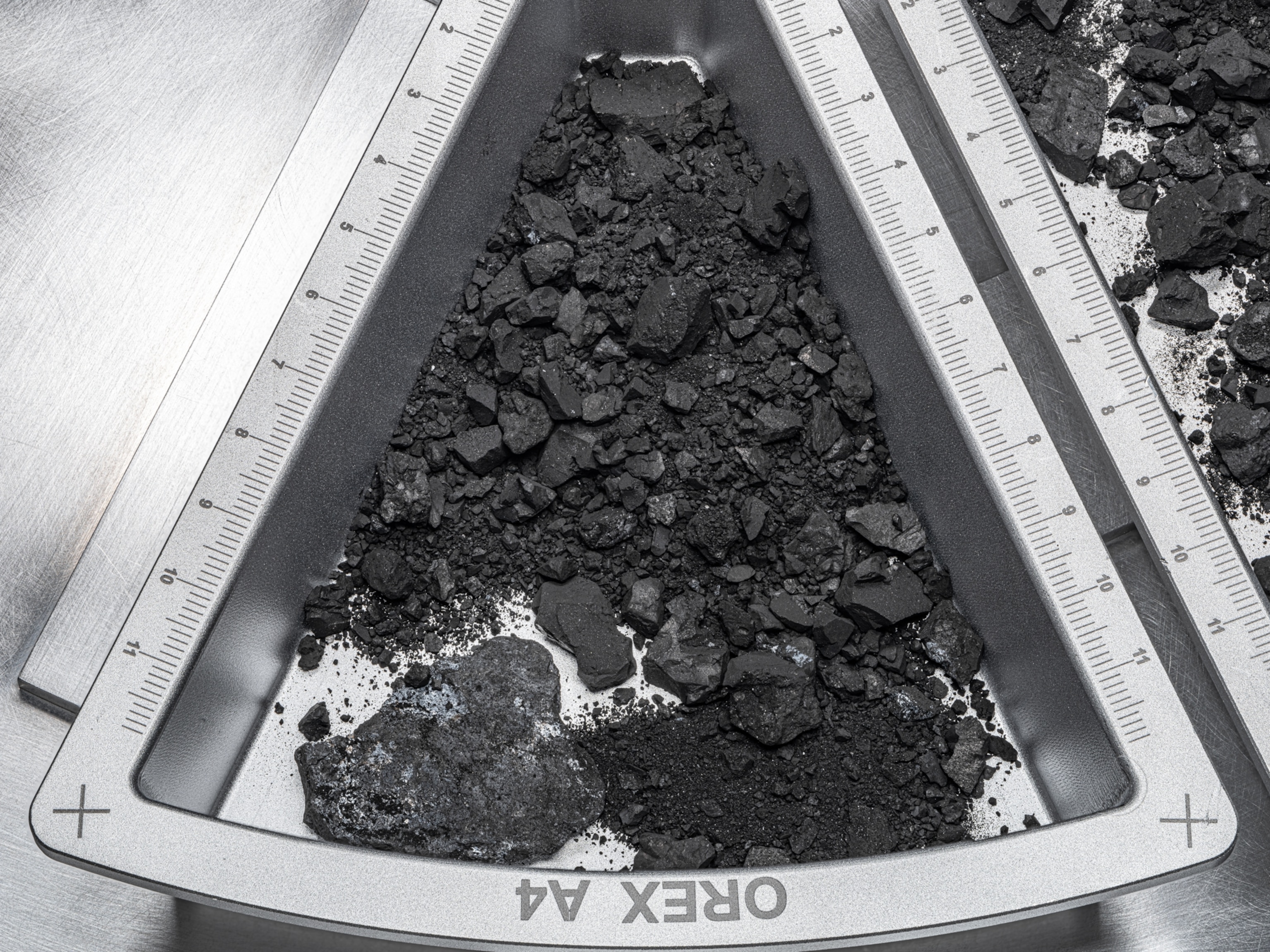

On October 20, 2020, a robot carefully scooped up 121.6 grams of the most expensive dirt in the solar system.

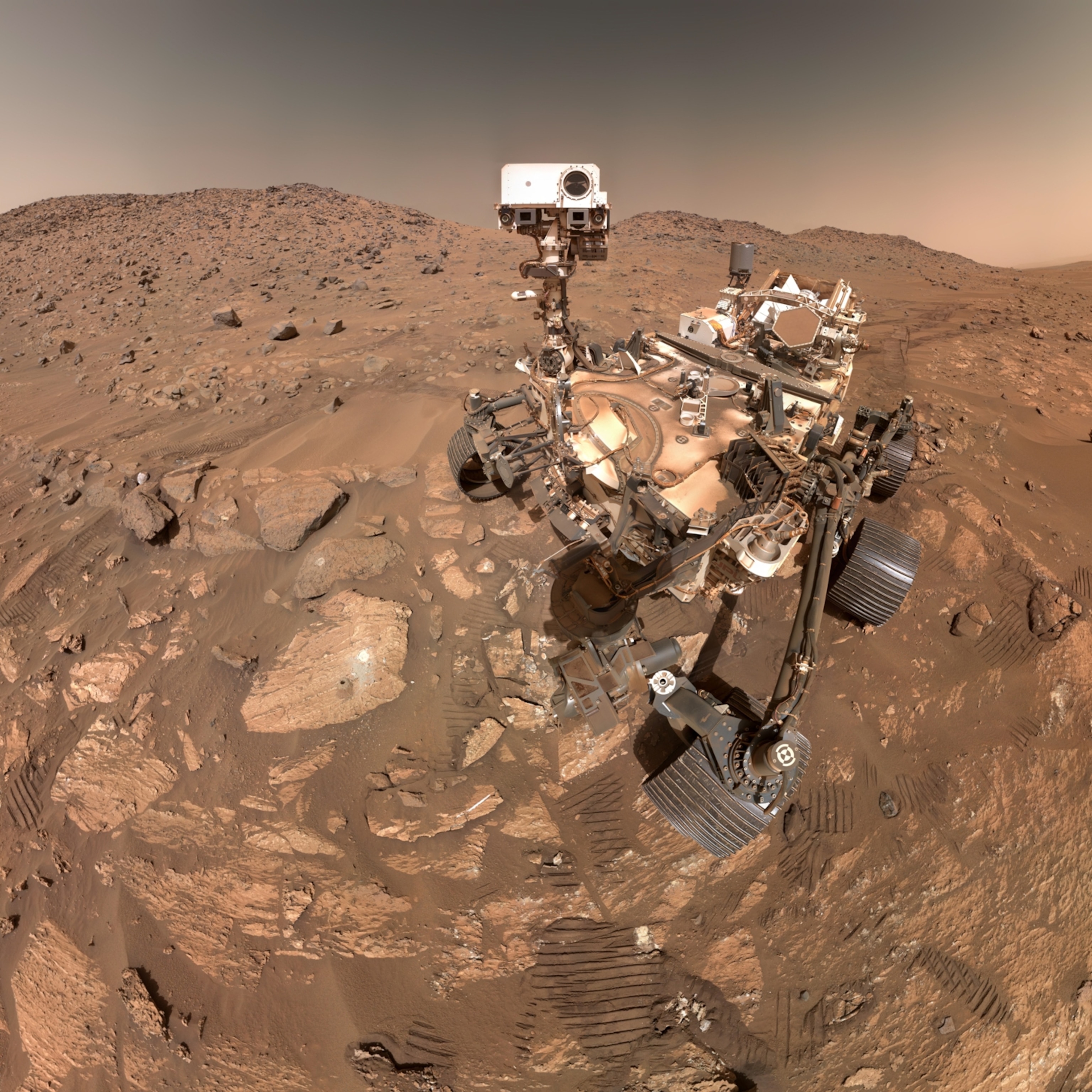

That robot, a NASA spacecraft called OSIRIS-REx, had spent two years en route to its rendezvous with the near-earth asteroid Bennu and two more observing it. Its 1.16-billion-dollar mission: Recover a sample from Bennu’s strange surface of loosely-bound space pebbles and return it to Earth. It succeeded, and on September 24, 2023, OSIRIS-REx dropped its carefully-packed sample capsule through Earth's atmosphere and into the waiting arms of eager scientists.

Bennu and a handful of special asteroids like it are ancient objects, leftovers from the very earliest moments of planet formation in our solar system. The sample OSIRIS-REx returned contains minerals that formed in water and a dazzling diversity of organic compounds, which contain carbon.

On our planet, organics are the stuff of life. But they’re the stuff of space, too—astronomers and planetary scientists are finding organics practically everywhere they look, from cold clouds of interstellar dust to icy moons to asteroids like Bennu. Sample return has revealed that Bennu sports a practical zoo of organics, including amino acids and other simple molecules that link together in life to form complex biological machinery. And just last month, scientists discovered sugars in Bennu that play vital roles in biology. Some scientists think these clues are a hint that the raw materials of life on Earth may have fallen from the heavens.

OSIRIS-REx isn't the only asteroid sample return mission. It comes on the heels of a Japanese effort, Hayabusa2, which returned 5.4 grams of rock from another ancient asteroid called Ryugu in 2020. By retrieving pristine specimens from these cosmic time capsules, scientists are revealing new details about the history of our own planet—and about where and how life might have emerged in the solar system.

(Inside the daring NASA mission to touch an asteroid.)

Cosmic time capsules

Some of our best clues about the earliest days of the solar system come from meteorites, or space rocks that fell to Earth. Less than five percent of meteorites belong to a special class called carbonaceous chondrites, which are practically as old as the solar system itself. They contain water bound up in rock and diverse organic molecules, from amino acids to simple components of DNA. Carbonaceous chondrites are like a snapshot of the chemical processes in the early solar system that set the stage for the origin of life.

“That is why we have used chondritic meteorites as a key to understand solar system formation and planet formation,” says cosmochemist Shogo Tachibana of the University of Tokyo, who led sample analysis for the Hayabusa2 mission. “But meteorites are always subject to terrestrial contamination.”

Before they end up in labs, meteorites endure a blazing fall through Earth’s atmosphere and often sit around on the surface for years to millennia. They’re exposed to the elements and our chemically reactive, oxygen-rich air. And Earth is wet and full of life, so contamination is a big problem—especially for scientists looking for hints of ancient water or organic molecules.

Sample return eliminates the contamination problem. It’s also our best way to check the telescope methods scientists use to study the millions of solar system asteroids we’ll never visit with spacecraft.

Reassuringly, the samples returned from Bennu and Ryugu look a lot like the most primitive carbonaceous chondrites. But they’ve also revealed plenty of surprises that show the importance of ground truths.

For instance, each amino acid comes in a “right-handed” version and a “left-handed” version; they’re mirror images of each other. Most natural processes produce a fifty-fifty mix of these two versions. But life is exclusively left-handed—for reasons scientists still don’t understand.

Previous studies suggested that primordial meteorites contain slightly more left-handed versions, so scientists wondered if life might have inherited its handedness from molecules that formed in space. But careful analysis of Ryugu and Bennu samples showed no bias towards left or right-handed amino acids—so even if organic molecules from space played a role in the origin of life, biology probably picked up its "handedness" on Earth.

(Bennu is also one of several asteroids that pose the greatest risk to Earth.)

How to build a blue marble

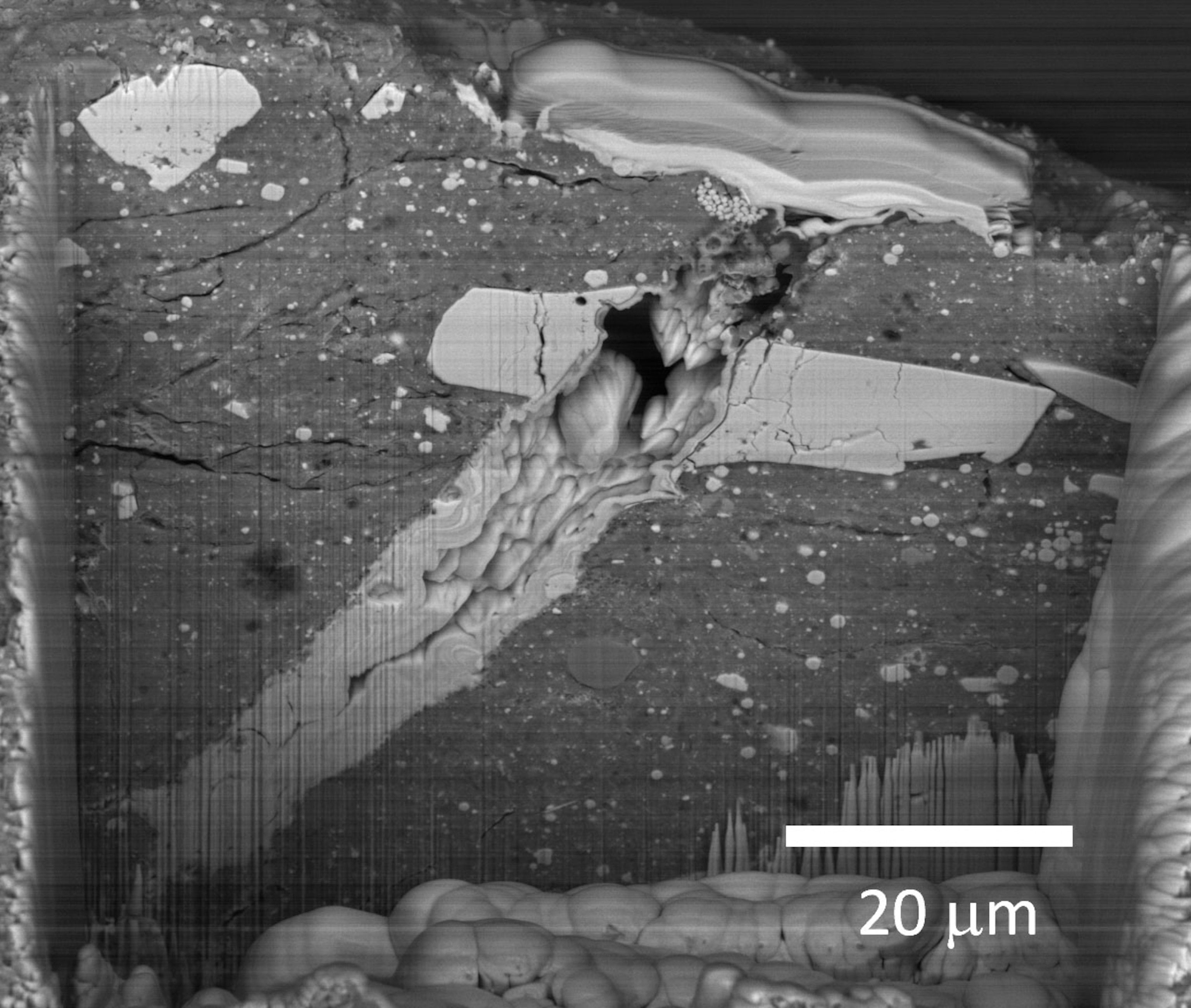

Scientists have also spotted minerals in Bennu and Ryugu samples that hold clues to one of the most enduring mysteries in planetary science.

“Why did we become an ocean world with this atmosphere and the origin of life?” asks University of Arizona planetary scientist Dante Lauretta, the principal investigator of OSIRIS-REx.

The rocky stuff that built our world was probably pretty dry. The planets coalesced out of a disk of gas and dust that swirled around the young Sun, and it was too hot for anything but rock to be solid in the region of the disk that became Earth. But further away, it was cooler. Beyond a “snow line” somewhere between the current orbits of Mars and Jupiter, water could freeze into solid ice and accumulate in nascent planets and other objects.

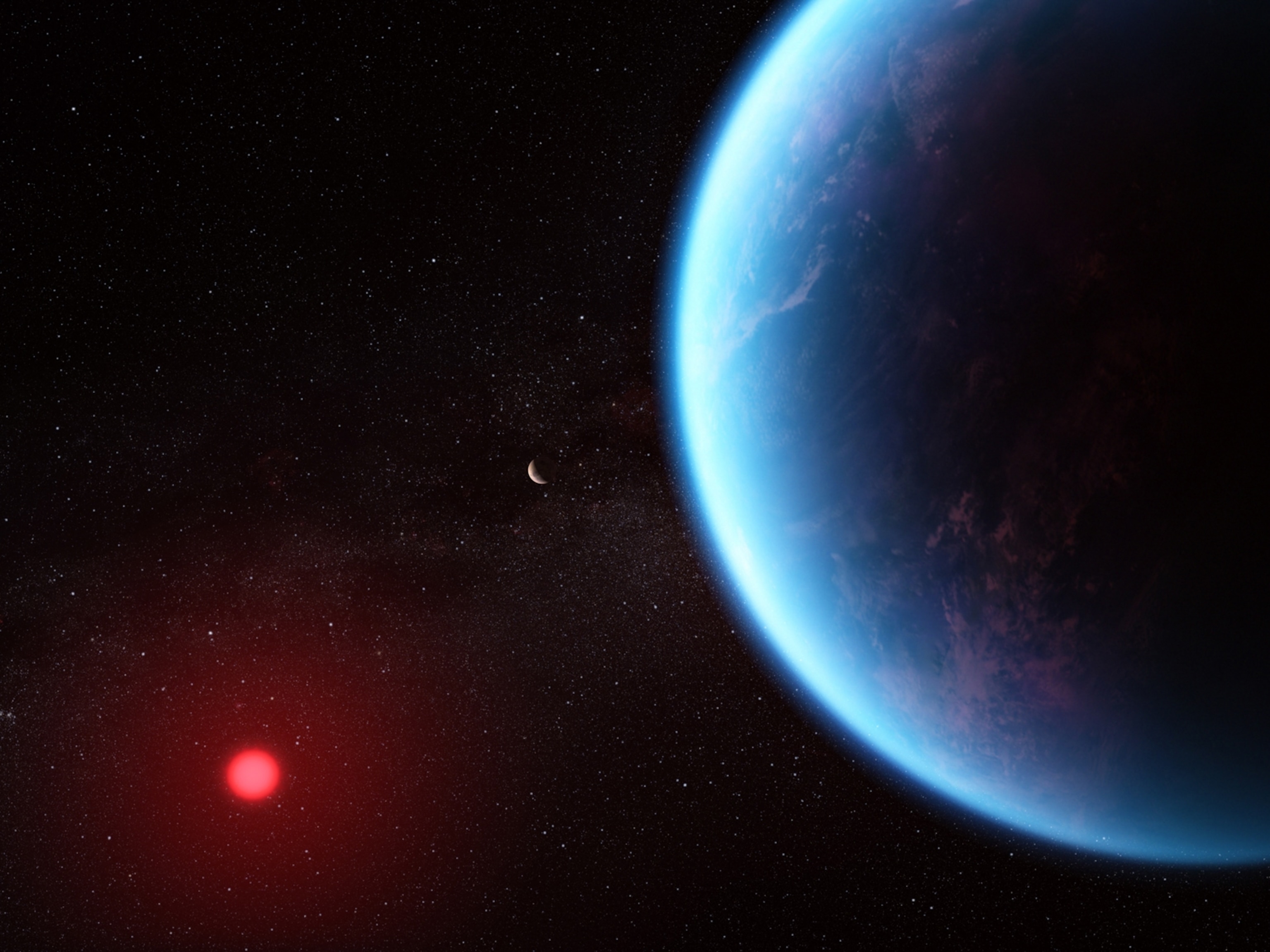

Scientists generally believe that at least some of Earth's water had to come from beyond the snow line, from material like Bennu and Ryugu. And the samples returned from these blobs of space rubble paint a surprising new picture of what that might mean: It’s possible that Earth received some of its water from hunks of dead ocean worlds.

Both Bennu and Ryugu contain clays including abundant serpentine, a mineral that forms at and below the seafloor where water reacts with rock from the Earth’s interior. Bennu and Ryugu are fragments of objects that got blasted to smithereens by violent planetary collisions in the early solar system. It’s possible that these objects were simply muddy dust balls crisscrossed by water-filled cracks. But Lauretta thinks the original source of Bennu and Ryugu might have been more like Enceladus or Europa—icy moons of Saturn and Jupiter that have oceans of briny salt water.

Other hints of the asteroids’ watery past lie in the samples’ fragile evaporite minerals that probably formed on Bennu and Ryugu when very salty water evaporated long ago. These minerals dissolve easily in water, so they’re very rare in meteorites. Some had never been spotted in meteorites before, says planetary scientist Bethany Ehlmann of the University of Colorado, Boulder.

In addition to the unique mineral finds, the Bennu sample also contained abundant ammonia—a simple nitrogen-containing molecule. It's possible that the organic molecules on Bennu, especially amino acids, formed via reactions in an ammonia-rich fluid. And minerals containing ammonia have been spotted on the surface of Ceres, a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, says Ehlmann. That’s puzzling, because the “snow line” for ammonia is even further out than the one for water, beyond the orbit of Saturn.

“So this is weird,” says Ehlmann. “The outer solar system has flung more material earthward than we previously than previously thought. There's something about early solar system dynamics that we're seeing clues to in the composition of these objects that we don't understand.”

(NASA prepares to explore alien worlds—by investigating Earth’s dark corners.)

How life began—and what it might look like beyond Earth

Water and other material from the outer solar system is not the only thing that asteroids like Bennu and Ryugu may have delivered to Earth—and to other worlds. Both bodies abound in simple organic molecules that are also found in life.

“There is increasing evidence that most, if not all, of the building blocks of life can form through multiple pathways in space and on the surface of planets,” says organic geochemist Angel Mojarro of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, whose team recently found tryptophan—an amino acid present in life that had never been detected in meteorites or samples returned from space before—in Bennu samples. With the same raw materials available practically everywhere, he adds, “my guess is that if there is life elsewhere, it will look very similar to life on Earth.”

Mojarro’s analysis found 15 of the 20 amino acids used to make proteins and all five molecular "letters" of the DNA alphabet in Bennu. And the recent addition of sugars to the list of organics by another team included ribose, a sole sugar component of DNA’s cousin RNA.

RNA is central to a leading hypothesis for how life began on Earth. “The first life might have organized solely as RNA. Not DNA, not protein, just RNA,” says Yoshihiro Furukawa of Tohoku University, who led the sugar study.

Together, the findings show that the geochemistry that played out inside ancient asteroids produced the raw materials of proteins and RNA. But we’re still a long way from tracing the roots of the tree of life back to an asteroid.

We know that the early Earth was bombarded by space rocks, but even dropping mountains of pure sugar into the ocean would do little to sweeten it. Unless the organic molecules that fell to earth somehow ended up concentrated together somewhere, they couldn’t spring to life. The mystery of life’s origins is not a missing magic ingredient—thanks to studies of meteorites, lab experiments, telescope observations, and now sample return, we know that simple organic molecules form readily throughout the cosmos. The real mystery is the process by which those organic molecules organize into life, and the environment that enables this transformation.

Still, whether or not life originally assembled from heavenly building blocks or organic molecules that formed on Earth, asteroid sample return still has lessons for scientists about how rocks give birth to biology. The organic molecules in Bennu and Ryugu formed in environments that look similar to the deep-sea hydrothermal vents some scientists think may have been life’s primordial cradle.

“What we have from the Bennu samples is an environment where there was no biology—where there were only geologic processes taking place. So that tells you the kind of organic chemistry that was likely happening in the ancient hydrothermal vents on the early Earth” says Lauretta. “We can use that to start testing ideas for the origin of life.”